Our History

Founded in 1916 in Dallas. Over a Century of Tradition. …The Model Tailors in Deep Ellum was where the black and white worlds of Dallas converged. The customers included underworld characters Benny Binion and his number two man, Harry Urban; George “Machine Gun” Kelly; and Joe Civello, a local Mafia boss. But a cross-section of upstanding Dallas men bought clothes there as well, including prominent blacks: civil rights leader A. Maceo Smith and blues musician Blind Lemmon Jefferson. To many blacks, clothing from The Model Tailors was a status symbol. “They had to have a Model Tailors suit,” Isaac Goldstein recalled. “Good slides [shoes], a good hat, and a Model Tailors suit.” The suit Blind Lemmon Jefferson was wearing in the only documented photograph of him was likely from The Model Tailors, and for him it was emblematic of his newfound success in the mid-1920s. By then, Jefferson had become the most significant blues singer to perform in Deep Ellum. His life and career epitomize the downhome blues of his generation…

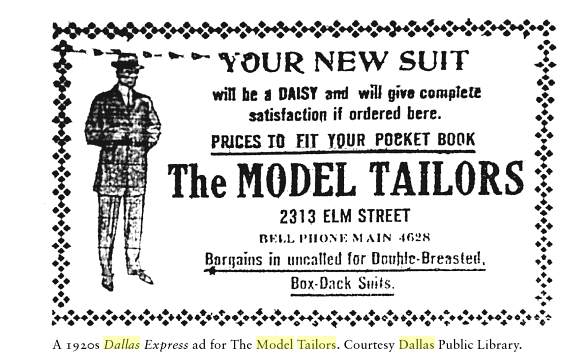

From Dallas Public Library archives about Model Tailors.

1920’s ad for Dallas newspaper.

Behind the doors of Model Tailors once told a man who could make clothes talk. This Merlin of tailors came to the U.S. at the age of 17 to escape Mussolini, smuggling with him one of Italy’s proudest and most ancient secrets: an intimate knowledge of the craft of clothing. After working through dark times in depression-era Pittsburgh and darker times fighting against Mussolini’s Axis powers as a member of the U.S. Army, the tailor finally found stability as a craftsman for the original Neiman-Marcus in downtown Dallas. Years later he bid adieu to his friend and employer, Stanley Marcus, who once called the tailor Italy’s all-time best export.

After his departure from Neiman-Marcus, Model Tailors master tailors cultivated a reputation as a true craftsmen. A decade later he acquired Model Tailors, and through word of mouth alone, this firm of over two hundred specialized clothiers got all the work they could handle with celebrities Henry Fonda, Charley Pride, and Billy Gibbons amongst their long list of clients. People are still talking to this day. Business still comes without the need for advertising.

I first heard about Model Tailors several years ago from a friend, and I could not be more pleased with the recommendation. Customers can expect uncannily precise alterations, beautifully crafted suits hand-tailored from the best Italian and British fabric, and a great dose of Italian hospitality compliments of Domenica, who was the only employee when I first patronized the shop.

Unlike modern tailors, many of whom receive two years or less of specialized education, Domenica and Mr. Cercone grew up in an era when sacrifice in childhood led to thriving success as an adult. Mr. Cercone circumvented bustling parks and groups of friends after school for years on the way to his apprenticeship, but when he reached the age of 17, he held the title of master clothier. “My boss was six when he started,” explained Domenica. “When you were young, after school you go the tailor and you learn.” As a result these masters enjoyed unparalleled stability in employment. This stability carried Mr. Cercone through one of the most economically trying times in U.S. history: “Even during the depression, you find a job because you have a trade.” In spite of this dependability, the vast majority of today’s youth do not show up for an apprenticeship promptly after school; they direct their attention elsewhere.

Many temptations hamper the youth of America from paving their way to a productive and secure, albeit predictable, adulthood. A growing sense of procrastination deters them, as does globalization and the unyielding expansion of competitive advantage. The allure of electronic devices, including phones, television, and video games, discourages the blossoming of ambition. Even what seems the most righteous and character-building pastime of today’s children, extracurricular sports, leaves old school craft workers like Domenica baffled: “If you take a sport, how are you going to find the time if it isn’t going to be your profession?” Several European countries still put an impetus on learning a craft, but many individuals shun the idea, even if the opportunity is right at their fingertips.

Tailors, and craft workers in general, do not get two weeks of vacation. They typically work at least six days a week, and the word “retirement” is not always in their vernacular. Mr. Cercone worked until his death in 1998, leaving Domenica and two other aging clothiers. Domenica recalls the case of coworker Margaret Zuniga, who was 94: “She worked the week before she died.” These dynamics drive people away, but Margaret was not working at 94 because she had to – she wanted to work.

Craft working is playing an instrument that can take a lifetime to perfect and revisiting it every day with gratitude. One remark by Domenica struck a chord with me; she said, “People didn’t complain. Now we complain. A long time ago, people were happy, but they didn’t make money. Now people make money and they’re not happy.” Our newest generations segue digital lives into ever-more-productive ways of being while the dignity of quiet work slips into the shadows. Few in this new era still believe the tortoise capable of besting the hare. Meanwhile, twilight falls on one of the bastions of a near-forgotten age, those few who remain still perfectly content with just making a living.

written by Jack Leutz